This project straddles a variety of topic areas including:

- Natural Language Processing (NLP)

- Text cleaning & processing methods with the Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK)

- Term Frequency Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF)

- Neural Networks Classifiers

Introduction and Problem Statement

One important sub-field of AI, natural language understanding at the machine level, is the subject of this project. Here we’ll construct a neural network classifier model capable of reading scouting reports for NHL draft eligible players and identifying the position of the player with up to 97% accuracy. In a later post we’ll perform aspect based sentiment analysis in order to extract information from these same reports regarding player strengths and weaknesses. Throughout, we’ll address the important issue of how our models read text as well as where the shortcomings of these models exist.

Let’s start by reading one example of a scouting report used in this project. Can you tell whether this is a forward or a defender?

| There are a whole host of reasons to be skeptical about Smirnov. He’s small and not overly physical, he’s a mediocre skater at best and Penn State’s schedule was tame before the divisional games began. However, at the end of the day, Smirnov was one of the top scorers and playmakers in college hockey as a teenage freshman. His skill level and work ethic are high-end, and he has shown the ability to be a game-breaker at the college level. He can make some risky mistakes, but in general his great creativity and vision allow him to make tough plays seem routine. NHL scouts are tentative on him in part because of how slow he is for a smaller guy. But when considering all of his attributes, there is value here. Pronman, Corey. 2017. “Top 100 NHL Draft Prospects,” ESPN https://www.espn.com/nhl/insider/story/_/id/19416323/nhl-top-100-draft-prospect-rankings |

The player discussed in that report is a forward, but that is not explicit in the report. As human readers, we can arrive at the conclusion this player is a forward based on contextual clues, but it’s no simple task and requires that we know something about how the game of hockey is played (i.e. that forwards are more likely to be high scorers than defenders).

Our classifier model here isn’t going to learn anything about the game of hockey, however. Rather, in order to get our model to correctly identify player position, we’ll have to first turn our text data into something it can read and then train it on many hundreds of example reports. We’ll accomplish that first task using a TF-IDF vectorization method. This will result in each report being represented as a sparse vector which can be fed into our model.

If you’d like, you can watch me go end to end on this project in a short series of videos (40-50 minutes or so), which I will embed in this page as we go along. Otherwise, you can also just read along with my project description and results in this post. Some but not all code will be shared here as well.

Data Description & Preprocessing

As a subscriber to ESPN+, The Athletic, and FCHockey, I’ve been able to create a corpus of written scouting reports for NHL draft eligible players, which is what I use as the basis of this project. Due to copyright protection issues, I can’t publicly share the corpus I’m using here, but I will show a snippet of the dataframe.

In all, we’re working with 1,338 reports, ranging in word counts from roughly 60-300. Some reports do explicitly state the position of the player, but many do not. Additionally, the the words ‘offense,’ ‘offensive,’ and ‘offensively,’ have all been replaced with a placeholder (in this case, ‘ooohhhh’ is that placeholder). This was done for the sake of making sentiment analysis (which I’ll discuss in a different post) possible. As it turns out, statements like “He’s the most offensive player in the draft,” are a real challenge for pre-trained sentiment models.

The first part of the video series is below:

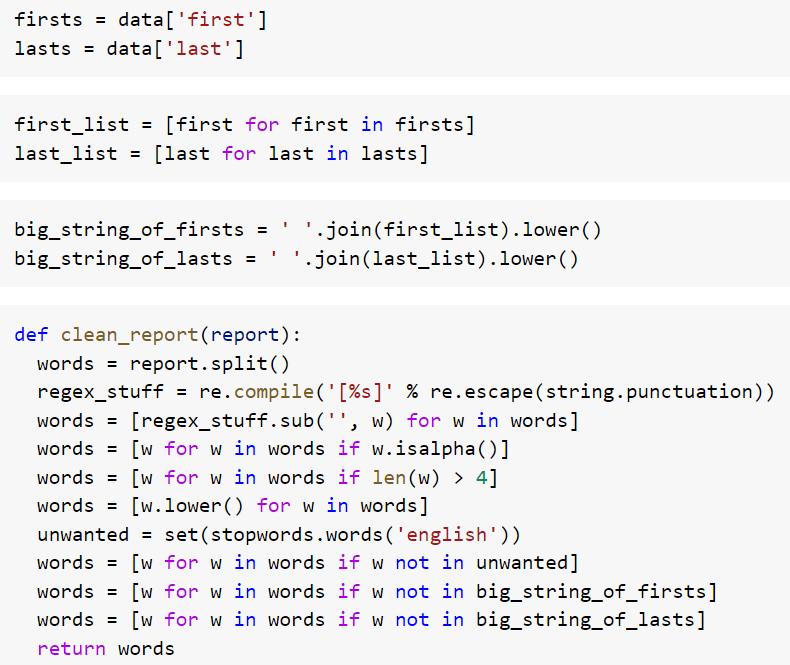

Preprocessing here involves removing all non-alphabetic characters, punctuation, and Stop Words (such as “it” or “what”). We also need to make all letters lower case and remove the names of the players, which are simply a noise factor. I also elected to remove all words shorter than 4 characters in length because experimentation showed this helps the classifier model as well.

The code to accomplish this is very basic, standard issue stuff. First we compile a large string containing all first names and last names (I did them separately here). Then, we create a function for cleaning each report according to what I outlined above and apply that function to the text. As a last step, we have to alter the datatype for each report from being a list of lists to a list of strings. This last step is simply a practical concern. I won’t go in depth in this post on how we’re leveraging things like the NLTK or RegEx module, but these are the basic tools necessary for the data cleaning in any Python based Natural Language Processing project.

As an example of what the text looks like by this stage, here is one excerpt from a fully cleaned up report: “naturally talented goalscorer skater lacks topend speed department elite acceleration burst standing position works along boards…” Note that the remaining text is missing many of the words necessary in correct English grammar. What we have not reads more like a wordy newspaper headline gone wrong.

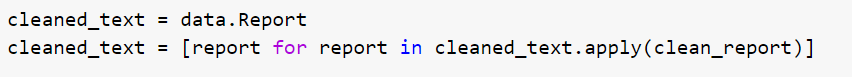

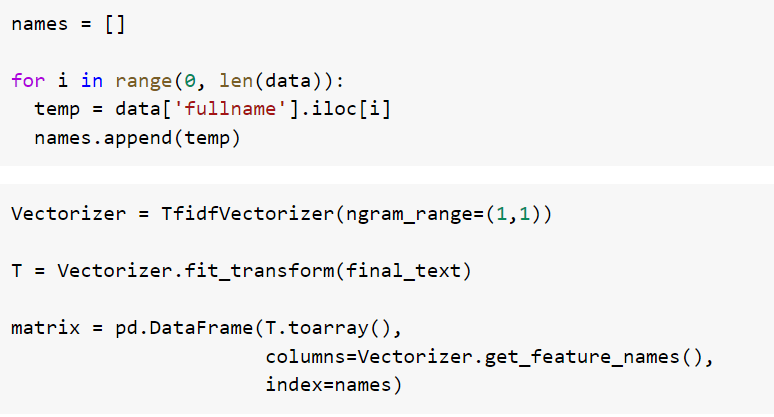

Finally, a document-term matrix is created which contains all known words within the corpus and TF-IDF scores for each document. I’ve chosen to place the player names into the index for readability purposes.

The final product looks like this:

If you’re unfamiliar with the TF-IDF method, all you need to know is that TF-IDF scores were created many years ago for use in optimizing search results. Although TF-IDF is not considered state of the art for search engines today, there is still value in the method.

TF-IDF scores are calculated by multiplying the number of times a word occurs in a single document by the inverse frequency of that same word across all documents. If a word appears zero times in the document, the score will be zero. If it appears in the document at least once, but is common to many other documents, the score will be very small. If it appears in a document at least once and is uncommon in other documents, the score will be relatively large. All scores are normalized between 0 and 1.

Methods & Modeling

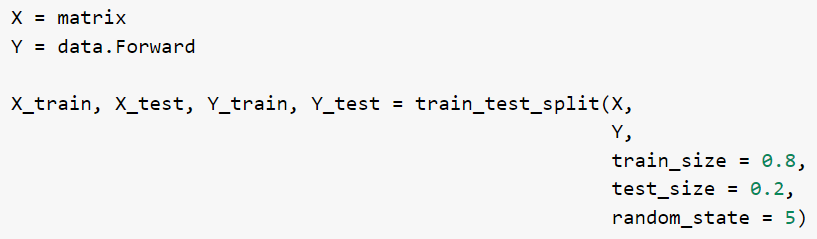

What we have now are sparsely populated vectors with a length of 6,549. This represents the number of total words in our scouting report vocabulary after applying the cleaning function. This will constitute the data our Neural Network classifier uses to determine player position. Next, we split this dataset up into 80% for training the model and 20% for testing it.

The network structure is quite simple. Our input layer consists of 6,549 nodes, one for each word in the corpus. We then feed this forward to a second layer of the same size with a dropout rate of 20% (this is done in order to help prevent overfitting). Our second layer then feeds all input forward to an output layer of two nodes, which is appropriate given that we are asking for binary classification.

The full code can be seen in the video below. For the purposes of this post however, I’ll just show the code used to build the classifier.

Results

Random changes to the training and test splits do affect our model accuracy somewhat, but we nonetheless see consistent accuracy rates between 93%-97%. The ROC curve from one particular run can be seen below.

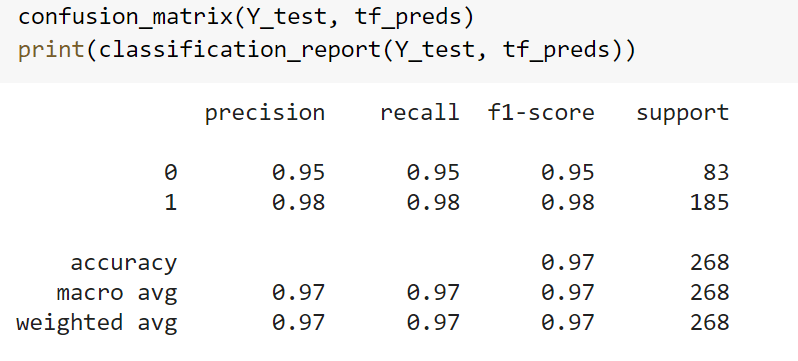

In the confusion matrix above, zero represents the defender class and one represents the forward class. It this particular trial, our model was tested on 185 forwards and 83 defenders. It correctly identified 181 out of 185 forwards and 79 out of 83 defenders.

In some instances, it’s easy to see why the model would struggle. Take the report below, for instance:

Salituro has had a very successful OHL career, and was his team’s leading scorer in 2014-15. He’s undersized, but is very gifted with the puck. He increased the tempo of his play a lot this season, making quick passes and decisions to disrupt defenses. His skating isn’t great for a smaller guy, but he moves at an above-average level in full flight. This remains an area for improvement.

In other instances however, we find that the model misidentified player position for reports where a human reader would never have made that mistake. Take the excerpt from a report for defense prospect Adam Boqvist, for example:

…[he’s] more of a long-term project than a lot of the other high-end defenders in this class… got one of the better shots among the defencemen in the class…

A 97% weighted accuracy score is likely as good or better than a human reader could do assuming they didn’t already know which players played which positions. However, there were still a couple of obvious misses, such as the one cited above.

Why is our Neural Network model incapable of correctly categorizing the report in which Adam Boqvist is explicitly named as a defender (not once, but twice)? Because the words ‘defender,’ ‘defenders,’ and ‘defensemen’ show up in reports for defensemen and forwards alike. For forwards, the statement might look like one of the following: ‘he has the speed to beat defenders wide,’ or ‘he can beat defensemen down low.’ In order to distinguish the difference between these statements and the statements we saw in Boqvist’s report, an attention mechanism is necessary. The model needs to be capable of reading reports not simply as a Bag of Words where each word, blind to dynamic context, represents a probabilistic nudge one direction or the other.

Further Discussion

Let’s close by looking briefly at which words are most associated with one position or another. Tree based models and regression models will make this a much simpler task than our Neural Network classifier. Although these types of models do not perform as well on the same data, their general findings are still useful. I go into a lot more detail in the video below, but in this post I’ll just point out some of the most interesting findings and relate them to the fact that we took the Bag-of-Words (context/order does not matter) approach.

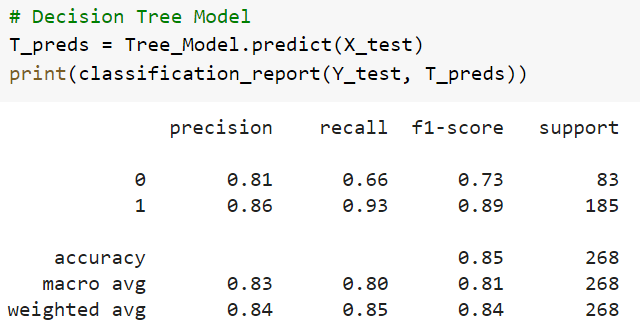

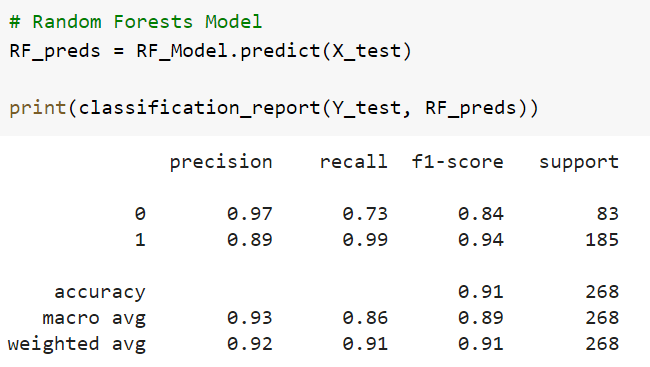

I put together three other models for the sake of comparison. One was a Decision Tree classifier, one was a Random Forests classifier, and one was a Logistic Regression model. Although none of these models achieved as much as our Neural Network classifier, their decision mechanisms are much simpler to interrogate. Because we took the approach that word order didn’t matter, the decision processes used in these simpler models are likely to give us a lot of information about the decision processes used in our Neural Network. Below are the results for each.

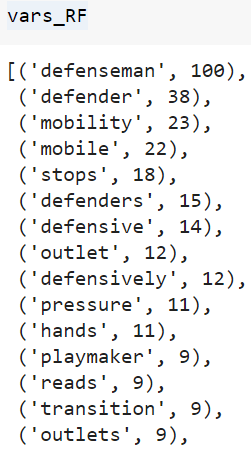

Between the two Tree based models, the Random Forests model is unsurprisingly a better option with around 91% (weighted average) accuracy. This model was better in every measure of precision and recall in every trial run I performed. Let’s look at the words this model considered most important. The image below displays the top 15 words in ascending order.

Note that the singular ‘defenseman’ and ‘defender’ both show up at the very top. The plural ‘defenders’ also appears.

Words we might not expect show up here as well, such as ‘mobility,’ and ‘mobile.’

But which direction do these words point? Which are associated with forwards and which with defenders? In order to determine this, we can either look at the simpler Decision Tree model logic or turn to our Logistic Regression model and pull out the coefficients for each word. Admittedly, the Logistic Regression model proved the poorest of the bunch, with a weighted accuracy of just 81% and a truly awful Recall of 46% for recognizing defenders. However, there is still some value here. I’ll start with the top 15 words for Forwards according to this model:

Note that ‘defenders’ plural is the second most likely word to appear in reports for forward position players.

Many of these words are unsurprising and make a ton of sense. For example, ‘playmayer,’ or ‘forward’ (singular), ‘center,’ ‘winger,’ ‘scorer,’ etc. But the inclusion of the word ‘defenders’ may seem perplexing at first. As it turns out, this word really does come up in many reports for forward position players, and it’s usually used to describe how that player ‘beats defenders wide,’ or ‘beats defenders to pucks,’ etc.

What’s most interesting here is how the singular version, ‘defender,’ impacts things. Below are the top 15 words for players at the Defensive position:

Here we see the singular ‘defenseman’ and ‘defender’ are the two best indicators that a player is actually a defender as opposed to a forward. The more subtle ‘mobility’ and ‘mobile’ appear here as well, which is apparently a descriptor for skating ability which is almost exclusively used when describing defensemen.

Final Word

Although our Neural Network model is doing something much more sophisticated, the results from the simpler models discussed above are still informative. Because we used a Bag-of-Words approach (which assumes that order and context do not matter), our model is incapable of distinguishing the important difference between sentences like “He’s one of those rare players with the speed to blow by opposing defenders,” and “He’s one of those rare defenders with the speed to blow by opposing players.” As far as our model is concerned, these are identical.

This gets us to an important point. There are massive differences between True AI and what we often use in the practical world. To the uninformed ear, hearing that a neural network is capable of identifying player position after reading a scouting report sounds impressive (and to an extent it is). However, the mechanism used to produce that result is important to remember. Here we’ve discovered a bit of a shortcut to identifying player position. Instead of requiring any real knowledge about the game of hockey, our neural network simply needs to be well trained on the shape of certain vectorized representations of those reports. This short-cut leads to excellent results in the aggregate, but also some surprising gaffes.