This project straddles a variety of topic areas including:

- Natural Language Processing (NLP)

- Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA)

- Aspect Based Sentiment Analysis (ABSA)

In Part I of this project we built an ensemble of BERT sentiment classifiers and asked it to classify sentiment at the sentence-level for corpus of NHL scouting reports. In part two we will put together a topic model which should give us some idea of what each sentence is about. Combining these two models is one way of conducting Aspect Based Sentiment Analysis.

Important Notes

Although I’ve chosen to do aspect based sentiment analysis at the sentence level, that would merely be a starting point in a more robust ABSA project. To reach the level of industry standard, an ABSA model should be flexible enough to drill down farther (because sentences can be about more than one thing), or zoom out as needed (because the topic of certain sentences may be implied by prior context). For the purposes of this first attempt however, we’re just going to look at what we can get from each sentence.

Anyone familiar with ABSA knows that the topic modeling algorithm I’ve chosen here, LDA, is an unorthodox choice for use at the sentence level. This is due to the fact that the LDA algorithm will struggle to find the co-occurrence patterns it seeks when it is applied to small documents or single sentences. However, the unique characteristics of our current corpus of documents (limited vocabulary and heavy reliance on common terms to name a few) help alleviate some of those issues. Further work will be needed in order to make this algorithm fully appropriate for use at the sentence-level, but the early results we find here are quite promising nonetheless.

Creating a Topic Model

If you prefer to see all the code, please follow along with the video series, which I’ll embed in this page as we go along. Otherwise, this post will walk through everything at a high level.

In part one we created a dataframe with every sentence contained in every report. Because reports are of variable length (some with up to 32 sentences and others with only 4 or 5), we used filler sentences to artificially balance the length of every report. Our first step here is to reshape that dataframe into a single stack, which can be seen below.

Note that we have 1,338 reports, each a of length 32 sentences, giving us 42,816 separate documents. As far as the LDA algorithm is concerned, there is no relationship between sentences of the same report. Each of these is viewed as a separate document.

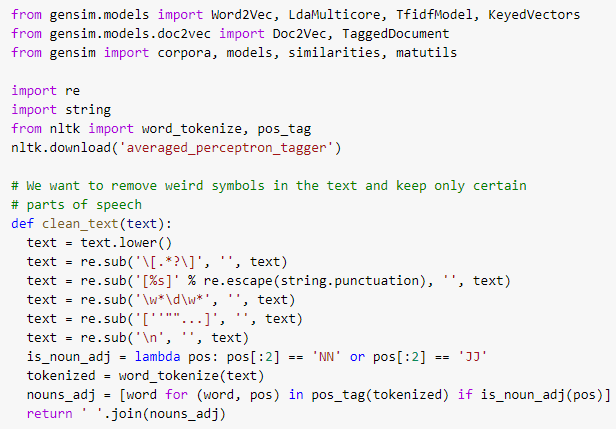

Next we need to write the text cleaning function for our corpus. Following a common practice and borrowing from the code of Data Scientist Alice Zhao, I’ve trimmed our corpus significantly by removing non-alphabetic symbols and all parts of speech except nouns and adjectives. The function itself looks like this:

Detail Note: Not shown in the above is a step which should be included – the removal of stop-words. In our corpus we also have many nouns such as ‘season’ and ‘player,’ which add nothing of value to the task of discovering true topics. I ended up removing these words and all stop-words in a separate step (you can watch the whole process in the video below,) but I would recommend simply adding these words to a list and removing them from the corpus in this one function. It’s faster and easier.

Next we need to create a term-document matrix and a vocabulary dictionary and then we can call the LDA algorithm to work. The term-document matrix holds each sentence as a row and each term as a column. This gives us a sparse vector representing each sentence.

The vocabulary dictionary contains every single word appearing in our corpus as well as an identifying number. This is necessary for calling the LDA Algorithm and will serve as the basis for the next stage of analysis as well.

Now that we have the necessary pieces we can call the LDA algorithm and obtain our topic model. The number of topics to search for is a necessary argument when calling this algorithm and I’ve chosen 12 topics for a few different reasons. First, this number seems intuitively about right. On a first pass, that’s usually good enough. However, I also happen to know from experimentation that adding more than twelve topics results in significant overlapping topic clusters, which is an inefficiency.

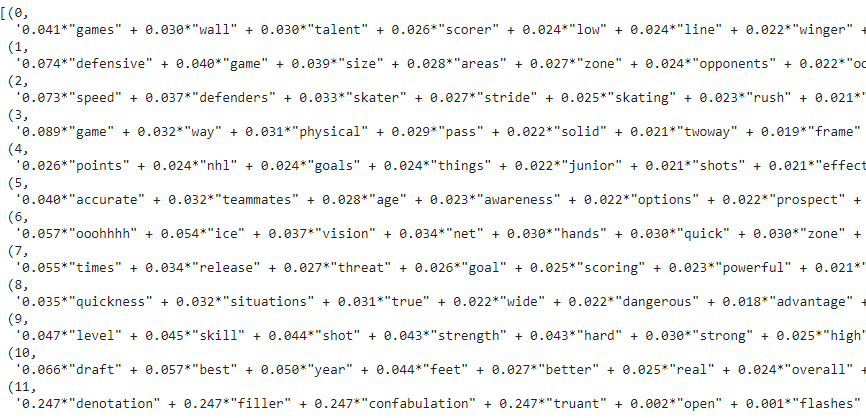

After running this algorithm, here are some of the top words associated with each topic cluster.

Although it may be difficult to pick out specific themes for some of these (topic five for example), others appear more promising. Topic seven seems to be about shooting ability and perhaps crosses over somewhat with topic nine, which seems to include several aspects of the overall skill of a prospect. Topic ten seems to be about placing the player in the overall rankings and how they’ve performed historically. Topic two is very clearly about skating ability. We also see that our filler sentence “filler confabulation betokening truant denotation” clustered nicely into its own category, which allows us to ensure these sentences do no harm to our overall analysis.

Sentence-Level Topics

The model we have now can tell us which topics each word in our corpus belongs to. Some words belong to many (example: the word ‘second’ belongs to categories 1, 4, and 10) and some words belong to just one (example: the word ‘draft’ belongs to category 10 exclusively). Additionally, the model gives us the probability that a given sentence belonging to a topic will contain a particular word. What I’ve chosen to do is sum these probabilities and nominate each sentence to the topic with the highest sum-probability score. There are other ways to do things, of course, but this is a reasonable way to begin.

How do we make this happen? The next two videos below go into great detail if you want to see this happen end to end. Otherwise, keep reading and I’ll hit the highlights.

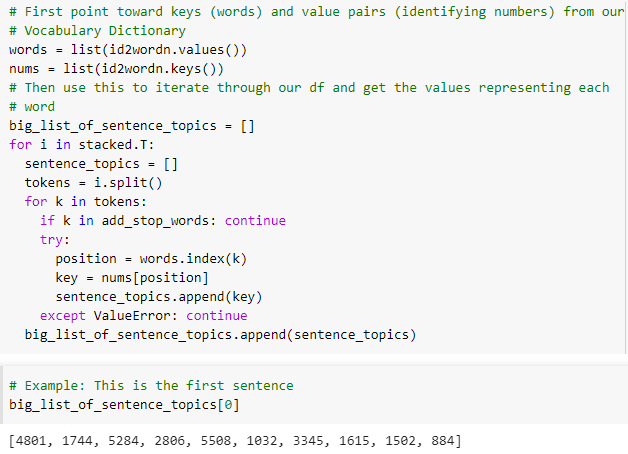

The first step here is to leverage the vocabulary dictionary we created earlier. The following code allows us to extract the key values from that dictionary and represent every sentence as a sub-list contained within a master-list.

The original sentence shown in the code snippets above read like this: “The second player tagged with ‘Exceptional’ status in the OHL — between John Tavares and Connor McDavid — Ekblad is the top player in the 2014 draft class.” – Corey Pronman, ESPN, “Top 100 NHL Draft Prospects.” https://www.espn.com/nhl/insider/story/_/id/10922527/corey-pronman-top-100-draft-prospects-index-nhl-draft-2014

Detail Note: it’s clear that removing player names would be helpful and I would recommend taking that step. I didn’t on the first iteration of this project and that should be changed in future. Had we taken this step, we could have removed some of the noise from this sentence and been left only with “second exceptional status draft class.” Incidentally, this would have resulted in no change to topic classification, but would have left a greater berth for the top topic, which happens to be the one we previously noted is about placing the player in the overall rankings or discussing past pedigree (topic ten).

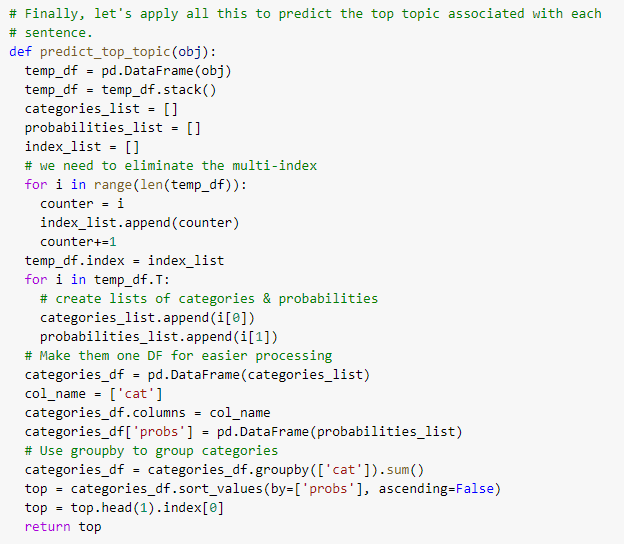

The next step is to define a function that will iterate through the master list of sentences represented as key values and extract probabilities from the LDA model itself.

As shown above, the function we wrote returns a list of variable length, containing sub-lists (also of variable length), containing tuples. Within each tuple is a category number in the first position, and a probability in the second position. We now need to mold this data into something more useable and a second function will help with that.

If we turn this master list into a dataframe and the stack it into a single column, we end up with a multi-index object like this:

We now want to get rid of the multi-index and one crude way of accomplishing that is to use the following loop:

This is admittedly an unsophisticated way of doing things, but our dataset is small enough that this works quickly. Quick and dirty is fine for now. Next, we need to put the pieces together in a single function capable of predicting the top topic associated with each individual sentence.

Running this on just that first sentence, which we pointed to earlier as ‘obj’ confirms that we have a working function. That sentence belongs to topic ten and our function identifies this:

Finally, we just need to apply this function to our stacked dataframe of sentences. For a variety of reasons (mostly involving our preprocessing steps), some sentences are now completely empty but still represented in the dataframe. Because of that, we also need to take the precaution of error handling. In this case, I have chosen to handle empty sentences by labeling them with their own topic number. This ensures my data outputs are of the same length I originally specified.

By looking at each error, we can confirm that the only issues came from empty sentences.

Our sentence level predictions are now all in one giant list. First we will change that list to a dataframe, then we’ll reform it so that the shape is more familiar.

Detail Note: Here again, this for loop approach may seem like a crude way of doing things. to an experienced programmer. It works okay for our purposes, so that’s all that matters at the moment.

After adding back the player names as the index, the resulting dataframe looks like this:

Here each sentence is a column and each player report is a row. We see mostly category 11 sentences because those are the filler sentences. The category 99 sentences represent sentences that can’t be categorized due to the fact that they are completely empty. This can happen for a number of reasons, with the most common reason being the use of periods in unexpected ways (such as with ellipsis).

Discussion of Results

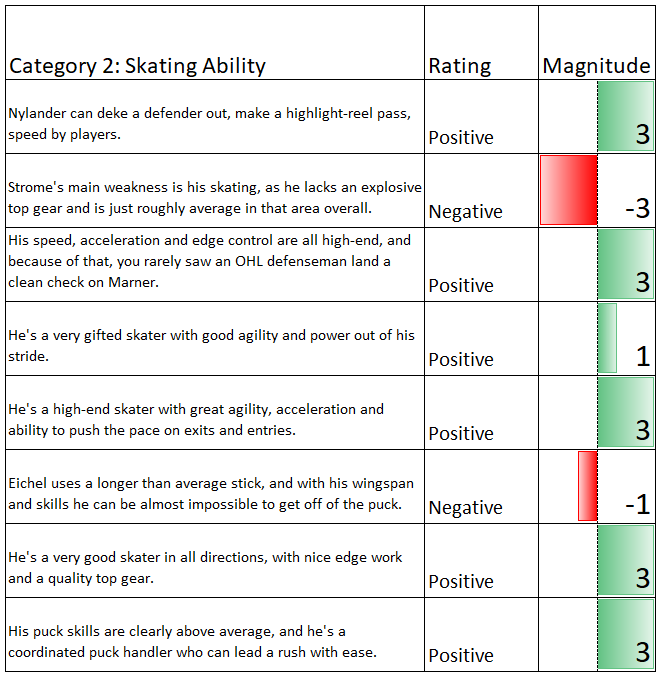

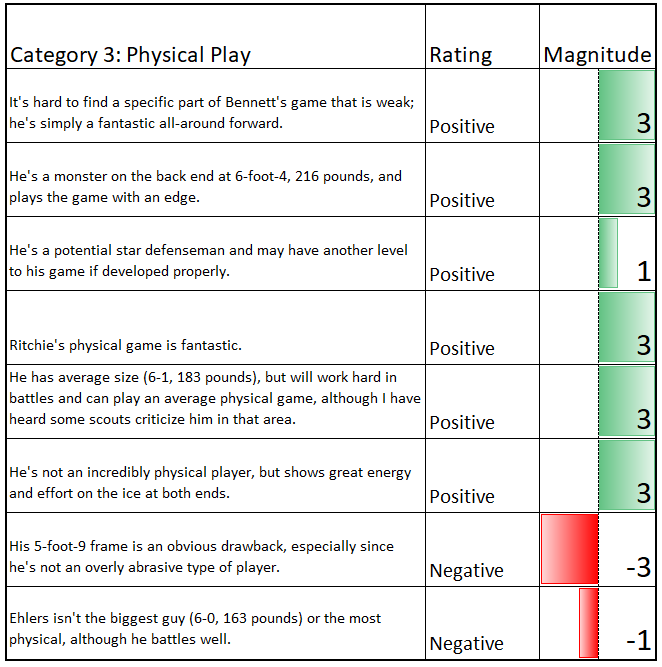

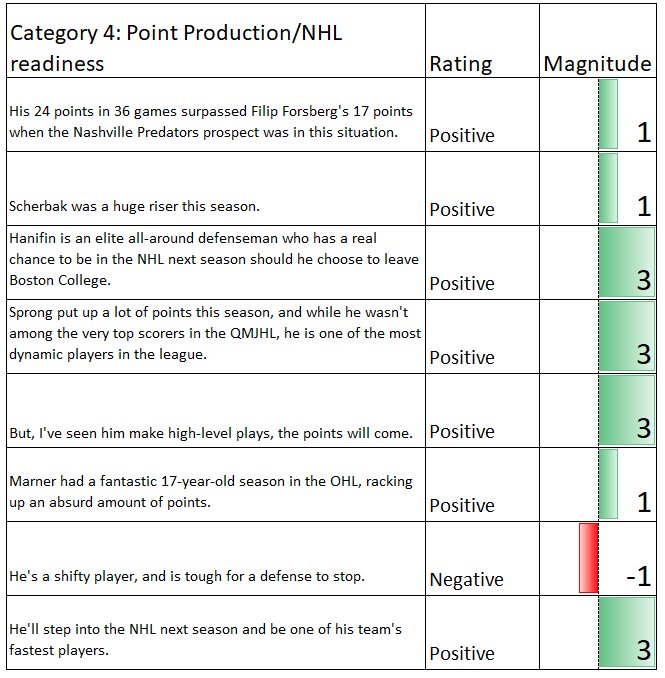

At some point, the assessment of results for any aspect based sentiment analysis has to come back to human review. Did we get what we wanted? Let’s look at a sample of sentences from the first three topic clusters and make the judgement as to whether they fit together. You can watch me walk through this in the video below, or keep reading.

In order to review the results of this analysis in an impartial manner, I took a sample of sentences from every category. This was done mostly at random, although in order to make the task as easy as possible, I only looked at the first 50 reports. Taking a truly random sample would be better, but I doubt my methodology affects much here.

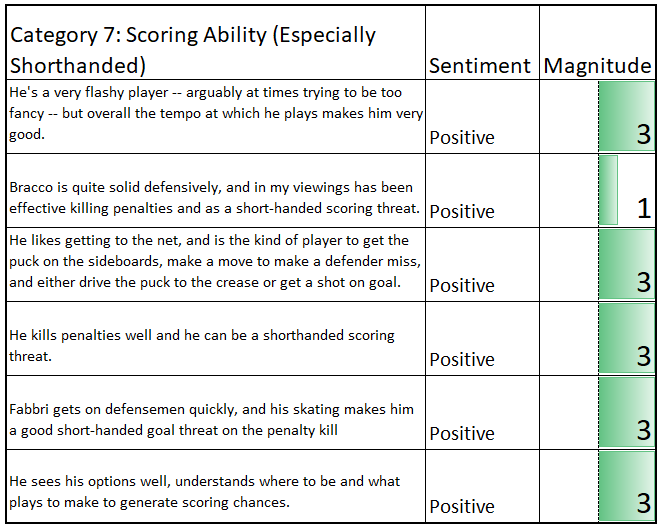

Defensive Ability & Penalty Killing

Skating Ability

Physicality

These topic clusters appear to fit together well. The second cluster in particular is an excellent example of exactly what we want to see, with every sentence mentioning something pertinent to skating ability except one. Generally speaking, these sentiment scores line up well also. However, there are varying degrees of success and some clusters are poorer.

Prior Production

Sense/Vision/IQ

Scoring Chance Generation

For the most part, the sentiment scores remain strong even if not entirely perfect. Certain sentences seem to deceive our sentiment model and there are things we would do on a second iteration to improve that. The accuracy of our topic model looks to be in full decline, however. Statistical point production makes sense as a cohesive topic, but too many off-topic sentences have found their way in. Hockey sense and IQ also makes sense in the abstract, but there are several sentences found within that cluster which do not belong. Category seven seems to present a different kind of problem – that scoring ability on the penalty kill is simply too niche to provide much value. Let’s close by looking at random sentence samples from the remaining clusters.

Failed Topic Clusters

What we see in these topic clusters is a lot of noise. Several of these sentences look like they belong in one of the earlier categories we created. Others seem to focus on things like overall skill level or shooting ability. This grouping of topics is not ready for analysis and suggests there are things we could do to improve our model.

Detail Note: If you’re counting clusters, I’ve only shown 10 so far and you may be wondering what happened to the other two. Cluster 11 was in fact our filler sentence cluster, so I’ve excluded it for that reason. Cluster 8 ended up being totally absent from the random sample I took. Looking at the words associated with that cluster and the probability of them showing up in it, I think the most likely explanation is that cluster 8 is an invalid topic cluster which lives in the shade of one or more larger clusters. This would seem to suggest we should use fewer clusters on the next iteration of this project.

Wrap-Up

In parts one and two of this project, we put together an excellent first pass Aspect-Based Sentiment Classifier using BERT and LDA. By combining three different BERT models which were minimally trained, we ended up with a sentiment classifier capable not only of seeing positive and negative sentiment, but also ambiguity. Despite the difficulty of applying LDA at the sentence level, we found that the limited vocabulary and heavy reliance on common terms found in our corpus made this approach viable, even if imperfect. We now have the ability extract information on skating ability, physicality, and defensive play with a relatively high degree of accuracy if we apply these models directly to text.

Future Work

Changes to our approach on a second iteration should include; better data preprocessing (i.e. removing more of the noise words from our corpus), training the LDA algorithm on larger, synthetic documents crafted from similar sentences, and smarter handling of sentences which appear to belong to a particular category only by a marginal difference over another.

What is meant by that last point is that many of the problem sentences I identified in this dataset were viable candidates for more than one category and ended up being assigned to a particular category only due to a marginally higher probability of belonging. Within this group there is often discussion of multiple attributes condensed into a single sentence. As discussed at the beginning of this post, the ability to zoom in beyond the sentence level is desirable, and identifying sentences which are legitimately about more than one thing is the first step to reaching this sort of dynamic model.